Part E: Jet fuel – infrastructure

PREVIOUS | NEXT | Return to CONTENTS

14. The capacity of the jet fuel supply infrastructure

14.1 This Part assesses the resilience of the system for supplying jet fuel to Auckland Airport:

- This chapter describes the capacity of the infrastructure making up the current supply chain and sets it against the historical and projected future demands for jet fuel.

- Chapter 15 assesses that capacity from a resilience perspective, using the standards provided by Fueltrac.

- Chapter 16 examines the reasons for the declining resilience of this supply chain and whether that could be reversed by new investment.

- Chapter 17 discusses possible alternative routes or supply chains for bringing jet fuel to Auckland.

- Drawing on the findings from these four chapters, chapter 18 summarises our analysis of the issues and our conclusions, along with our recommendations.

How we assessed the capacity of the jet fuel supply chain

14.2 The 2017 RAP outage highlighted that the supply chain that brings jet fuel to Auckland Airport is vulnerable to what is known as “single-point failure risk” at all points. That is, if the infrastructure at a particular point fails, there is no ready alternative that can keep the overall supply chain operating. As set out in detail in chapter 2, the supply chain involves the following process:

- The Marsden Point refinery refines jet fuel from imported crude oil.

- Once certified at Marsden Point, the jet fuel is sent to Wiri along the RAP.

- At Wiri, the jet fuel must settle for quality purposes, then it is re-certified and sent to the JUHI at Auckland Airport along the WAP (or in some circumstances, it is trucked to the JUHI).

- At the JUHI, the jet fuel must again be left to settle for quality purposes, then it is re-certified and pumped to the gate on the apron through the airport’s hydrant system.

- Finally, the fuel is pumped from the hydrant into the fuel tanks of the aeroplanes.

14.3 There are two key concepts for assessing the capacity of a supply chain like this: storage capacity provided by the tanks at each point (the refinery, Wiri, and the JUHI); and the throughput capacity or volume that can be moved through the two pipelines.

14.4 The storage of jet fuel stocks at points along the supply chain is important for resilience because it provides cover against surges in demand and supply interruptions, as well as a level of redundancy in case the infrastructure fails. All airports have some storage capacity or redundancy built into their supply chains, and there is international guidance to help work out the appropriate amount of protection.[1]

14.5 Along the Auckland jet fuel supply chain, fuel stocks are stored at the Marsden Point refinery, Wiri, and the JUHI at Auckland Airport. As the 2017 outage showed, these stocks can help the airport to keep operating while damage to the supply chain is repaired and while a temporary supply chain is established. They also help the airport manage stresses, such as surges in demand during peak travel periods, such as school holidays.

14.6 It is widely agreed in the industry that storing fuel as close as possible to the airport is the most important step for protecting against disruption, because no further transport is needed to bring the fuel to where it is used if the disruption occurs upstream in the supply chain.

14.7 Redundancy is also important in relation to pipelines like the RAP and WAP. For pipelines, redundancy is assessed in terms of throughput capacity, rather than storage. The pipelines need to have a certain amount of spare throughput capacity (measured against demand), which means that more fuel than usual can be sent down them if that is needed to cope with disruptions or surges in demand.[2]

The overall capacity across the supply chain

14.8 The Inquiry asked the relevant participants for detailed information on the capacity of the different parts of the supply chain. We then asked Fueltrac to assess that information. They calculated the days of cover provided by storage in the whole supply chain, using the figure of the average daily demand for jet fuel at Auckland Airport.

14.9 Their conclusion was that, in terms of days’ cover, there appeared to be approximately 10–14 days of jet fuel in storage at different stages of the supply cycle (with 10 days’ cover at the low point of the supply cycle).[3]

Forecast demand for jet fuel

14.10 The forecasts of expected demand are important for assessing resilience. They indicate what the system will have to cope with in the future. If demand is likely to increase, that is a stress the system will have to manage.

14.11 The Inquiry asked all relevant participants for their views on the future demand for jet fuel at Auckland Airport. As a result, we were provided with a report that had been commissioned by Auckland Airport and BARNZ in 2018. The report – Jet Fuel System Resilience and Capacity Review (the “2018 Capacity Review”) – was prepared by Hale & Twomey and WorleyParsons to provide a forward-looking view of the resilience and capacity of the Auckland Airport jet fuel supply chain.[4]

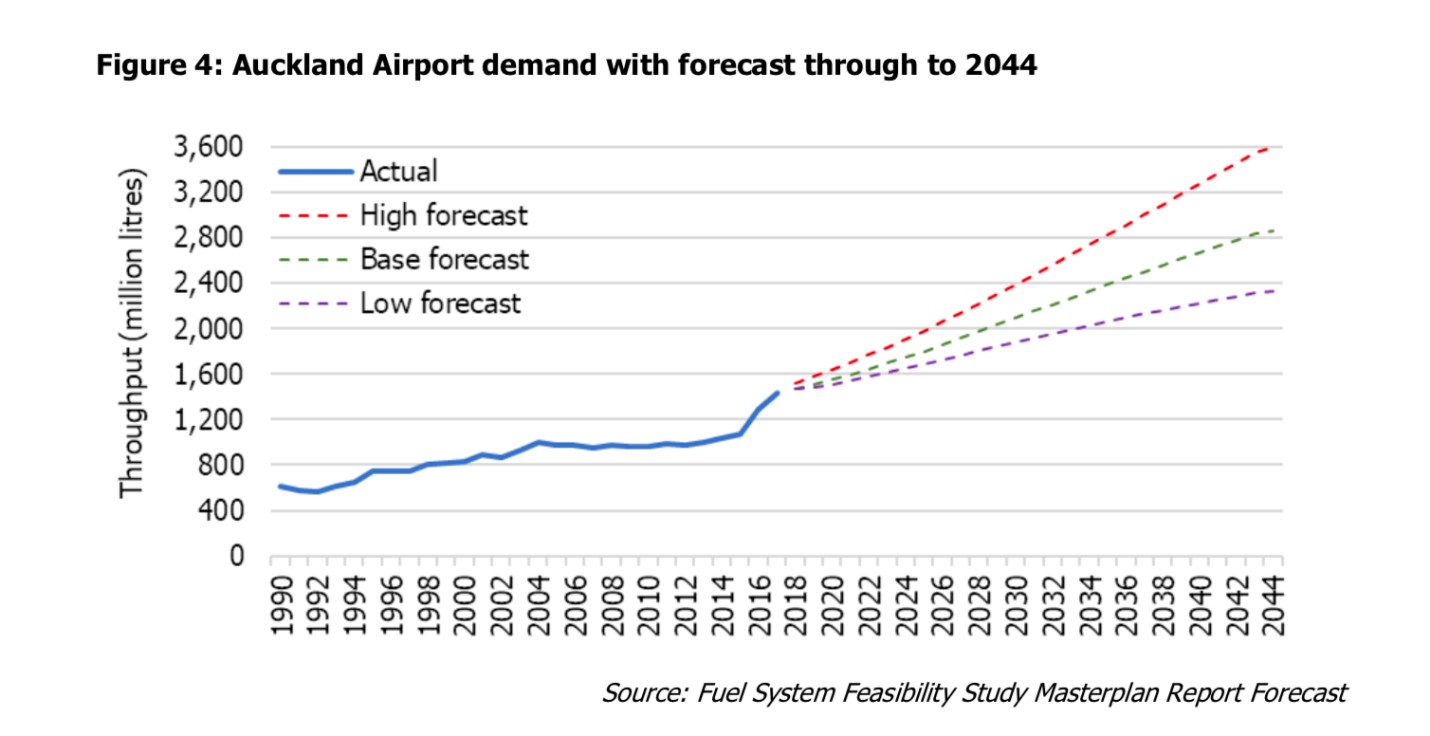

14.12 This report set out the forecast that is reproduced in Figure 12 (the “Jet Fuel Demand Forecast”). It shows jet fuel demand at Auckland Airport since 1990, as well as forecast growth on a high, base (mid) and low forecast from 2018 through to 2044.

Figure 12: Jet fuel demand forecast at Auckland Airport to 2044[5]

14.13 The data shows that the demand for jet fuel at Auckland Airport has doubled over the last 20 years. Half of that growth was in the last four years.[6] The main drivers of the recent high growth rates have been:[7]

- an increase in international passenger numbers (75–80% of New Zealand’s jet fuel demand is used for international flights);

- an increase in long- and ultra-long-haul flights, which require substantially more fuel than shorter flights, such as Trans-Tasman routes; and

- fuel prices – when fuel prices are lower, new or long-haul routes are more viable than when prices are high.

14.14 The Jet Fuel Demand Forecast assumed:[8]

- the main driver of jet fuel demand will continue to be an increase in the number of passengers;

- there will be “a continued increase in demand from a gradual move towards longer haul flights”; and

- the “high forecast likely reflects a more optimistic outlook for passenger growth and a larger impact from longer haul flights”.

14.15 On 30 May 2019, the Inquiry held a closed workshop with key participants.[9] During the workshop, most participants agreed that:

- the Jet Fuel Demand Forecast is the best available forecast of the likely future jet fuel demand at Auckland Airport;

- the high to base (mid) forecasts were the best forecasts to rely on; and

- growth in demand for jet fuel at Auckland Airport was somewhere between 3.5 and 4% a year (which sits above the base forecast).

14.16 The specific data points for the Jet Fuel Demand Forecast through to 2040 are set out in Table 9.

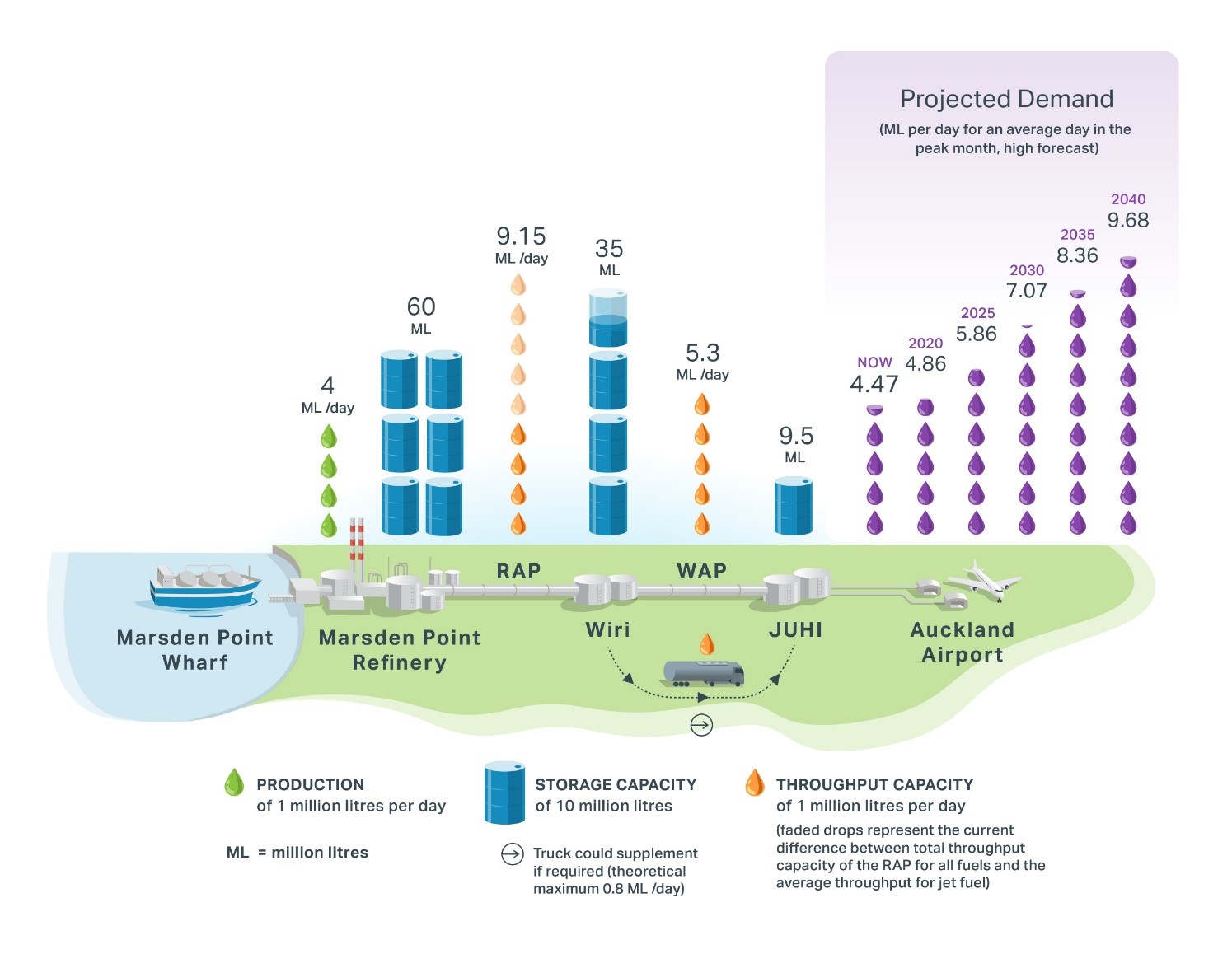

Table 9: Updated forecast jet fuel demand for selected years to 2040[10]

14.17 We acknowledge that forecasting is an imperfect science and that forecasts will change over time. However, we consider growth in the range of 3.5–4% a year to be a realistic assessment of the likely future demand (which is between the base (mid) and high forecasts). Given the way that demand is tracking, it is prudent to use this range when thinking and planning for resilience purposes. If demand increases in accordance with this range, Table 9 indicates that:

- by 2030, Auckland Airport will require somewhere between 600 and 900 million litres of additional jet fuel each year; and

- by 2040, Auckland Airport will require somewhere between 1.2 and 1.8 billion litres of additional jet fuel each year.

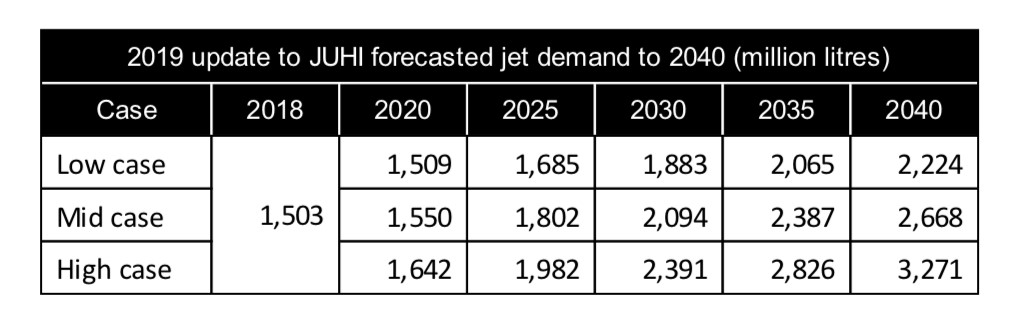

14.18 We now turn to assessing how well the infrastructure in the supply chain will cope with this increasing demand. Figure 13 illustrates the capacity of the existing system along with the forecast increases in demand.[11]

Storage capacity

Storage at Wiri

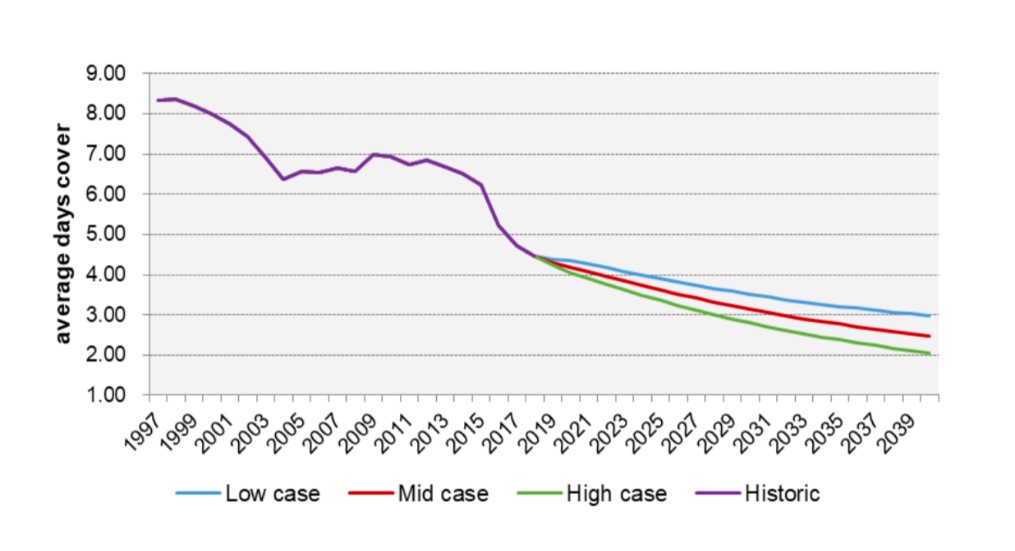

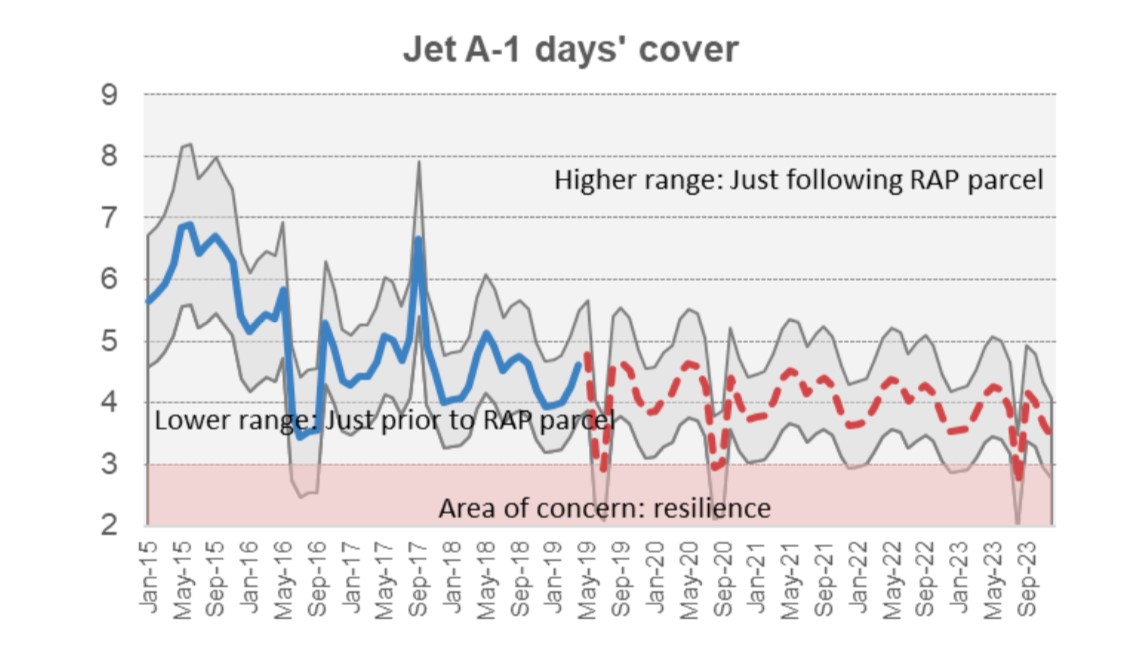

14.19 In the 2019 WOSL Report, Hale & Twomey modelled the impact that the Jet Fuel Demand Forecast would have on days of storage cover at Wiri. Figure 14 shows the average days’ cover provided by Wiri from 1997 to 2019, as well as the forecast days’ cover out to 2040 based on the high, base (mid) and low forecasts. This graph assumes no further investment in infrastructure at Wiri.

Figure 13: Capacity of jet fuel infrastructure and forecast demand

Figure 14: Average jet fuel days’ cover forecast at Wiri to 2040[12]

14.20 The graph shows there has been no increase in the storage capacity at Wiri since the mid-1990s. Over time, the days’ cover at Wiri has been reducing. It is now approximately half of what it was in the mid-1990s.[13]

14.21 Figure 14 shows a particularly sharp drop in the amount of cover in the last four years. Cover levels are now significantly lower than at any other time in the past, averaging a little over four days. Average cover in 2019 is expected to be around 60% of the level it was in 2014.

14.22 Figure 15 goes into more detail. It shows that in peak demand months, the cover at Wiri just before the delivery of a batch of jet fuel from the RAP is only slightly above three days. This low point is set to fall below three days by 2022. The graph also shows the impact of routine tank maintenance proposed for 2019, 2020, and 2023, with sharp drops in cover coinciding with a jet fuel tank being out for maintenance for an 8-week period.

Figure 15: Average jet fuel days’ cover forecast at Wiri in the medium term[14]

14.23 Hale & Twomey also noted that the jet fuel system needs a certain amount of stock to operate (in that the amount of stock cannot be reduced to zero without causing a disruption to the subsequent jet fuel supply). When the buffer stock is removed from the calculation, the amount of cover is even lower than that indicated by the lower range in Figure 15.[15]

Storage at the JUHI

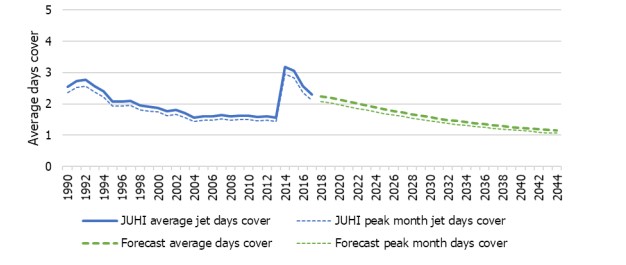

14.24 The 2018 Capacity Review set out the average days’ cover at the JUHI from 1990 to 2018, and then modelled the estimated cover out to 2044 based on the base (mid) forecast (see Figure 16). Again, the modelling assumed no further investment in infrastructure.

Figure 16: Average jet fuel days’ cover forecast at JUHI to 2044[17]

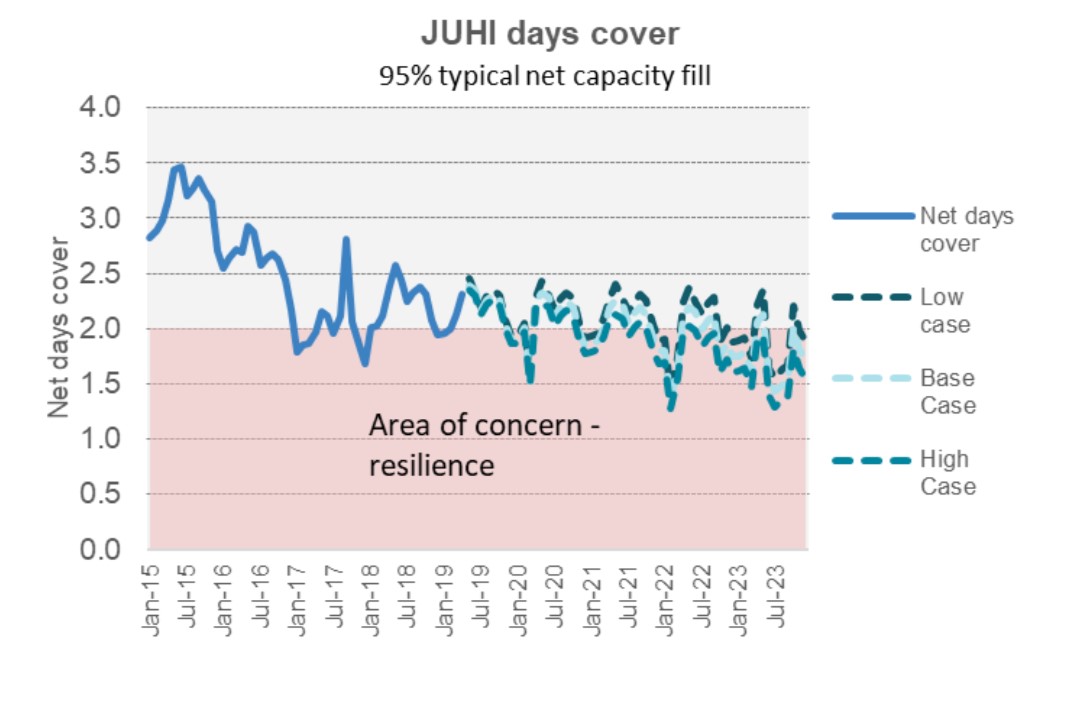

14.26 There is currently around two days’ cover at the JUHI. Cover is less than two days during peak demand months.[18] Figure 17 shows that the number of months in which storage cover falls below two days is expected to increase during the next two years.

Figure 17: Forecast reduction in days’ cover at the JUHI to July 2023[19]

14.27 In 2023, the two large tanks at the JUHI are scheduled to be taken out of service for their 10-year inspection. As with Wiri, there will be a significant reduction in the level of days’ cover at the JUHI while these tanks are out of service. For that period, the three fuel companies will need to rely more on the storage at Wiri, which we have already found is limited.[20]

Throughput capacity in the two pipelines

Throughput capacity of the RAP

14.28 The RAP currently delivers approximately 126 million litres of jet fuel to Wiri in a typical month.

14.29 As we noted in chapter 2, Refining NZ is scheduled to start testing the use of a drag-reducing agent in the RAP later this year. The drag-reducing agent cannot be added to jet fuel, but it will increase the throughput of petrol and diesel being sent down the pipeline, meaning that time will be freed up for more deliveries of jet fuel. The expected gain is about 15% more capacity.

14.30 Refining NZ also told us that it is in the process of seeking the consent of Lloyd’s Register (the external certifier) to increase the RAP’s maximum operating pressure from 75 barg to 82 barg. It expects that a Certificate of Fitness for the pressure increase will be issued later this year, ahead of the 2019 peak demand period.[21]

14.31 In May 2019, Refining NZ modelled the capacity of the RAP against the Jet Fuel Demand Forecast. Their results showed that using a drag-reducing agent with petrol and diesel fuels from 2020 would result in the following changes:[22]

- In the likely growth scenario, the pipeline’s existing capacity would be sufficient to meet expected demand through until 2035, and then its capacity would be constrained only in the peak month (December). Refining NZ told the Inquiry this constraint could be managed by drawing down Wiri’s stock during December (taking advantage of spare pumping capacity in November and January).[23] With this step, Refining NZ believed that the RAP capacity would be sufficient to meet jet fuel demand through until 2045.

- In the high-growth scenario, the RAP would start to become constrained in the peak demand months of December and February from 2029 onwards. Refining NZ said at this point, it would be able to meet jet fuel demand by reducing Waikato-bound petrol and diesel volumes that passed through the RAP to Wiri and instead, sending that fuel by coastal tanker to Mount Maunganui. If this occurred, Refining NZ said the modelling indicated the RAP’s capacity would be sufficient to meet jet fuel demand through to 2045.

14.32 One of Refining NZ’s customers told the Inquiry that, in its opinion, it was unlikely that Refining NZ’s existing infrastructure would be able to keep pace with future demand growth for both jet fuel and ground fuels in Auckland. The customer also said it was planning to divert ground fuels from the RAP in the final quarter of 2019 and the first quarter of 2020 and instead, would deliver them via the Marsden Point truck-loading facility or Mount Maunganui.

14.33 We put this comment to Refining NZ. It advised us that the RAP currently has surplus capacity to supply ground fuels and jet fuel into Auckland, which is allowing the RAP to be used for the supply of fuel south of Auckland into the Waikato. To the extent that any adjustments to supply are needed to cover the peak demand months of December 2019 and February 2020 (should the RAP not be operating at 82 barg), Refining NZ said these will simply result in a shift in the supply of ground fuels into the Waikato (via Mount Maunganui).[24]

Throughput capacity of the WAP

14.34 The Inquiry understood that the WAP can currently achieve a maximum throughput capacity of approximately 5.3 million litres per day.

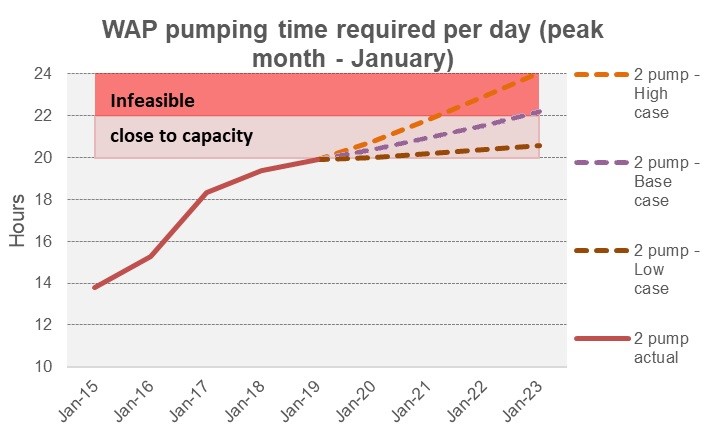

14.35 In its May 2019 report prepared for WOSL, Hale & Twomey observed, in relation to the WAP:

Even with two pump operation in peak months (December/January) pumping is now required 20 hours a day, taking it close to maximum capacity. Within five years on the mid forecast, this will rise to a 22 hour[s] per day.[25]

14.36 These capacity issues are illustrated in Figure 18.

Figure 18: WAP pumping time required per day over the peak month of January[26]

14.37 Figure 18 also shows that if demand follows the high forecast, pumping will be required for 22 hours per day in peak months as early as January 2021, and pumping will reach maximum capacity (i.e., 24 hours per day) by January 2023. We understand that pumping 24 hours per day is not feasible because the pumps need to be turned off for ordinary maintenance activity.

14.38 Jet fuel can be trucked from Wiri to the JUHI if the WAP is unable to meet demand. An exercise was conducted in September 2018 to assess how much fuel could be moved by truck over a 23-hour period. In that trial, 0.8 million litres of jet fuel was delivered to the JUHI through 24 trips, using four trucks and eight drivers.[27]We understand this to be about 18% of January 2019 peak month demand.[28]

14.39 However, this figure should not be taken as a realistic indication of the amount that could be trucked in practice. Not only would it require modifications to the JUHI to improve receipt capacity but it would also create traffic management problems at Auckland Airport. Auckland Airport told the Inquiry that it does not consider trucking to the JUHI to be viable at the moment, other than on an exceptional basis. They said this was because the core precinct’s domestic access roads have to be completely closed twice for each truck delivery and this has a significant impact on the operations of the domestic terminal.[29]

14.40 Z Energy provided the Inquiry with analysis that, based on annual growth of 3.5% a year to 2035, and with no further investment in infrastructure to increase throughput capacity:[30]

- there will be insufficient WAP capacity to meet December 2019 demands, and the shortfall will have to be trucked to the airport;

- more trucking from Wiri to the JUHI, or additional WAP capacity, will be needed as early as February 2023 to prevent JUHI stocks from being negatively affected – in other words, JUHI tanks will not be able to be kept full, which will reduce the cover they provide; and

- peak days will not be manageable after 2024 using the WAP supplemented by trucks.

14.41 If Z Energy’s analysis is correct, an infeasible volume of fuel would need to be transported by truck to the JUHI at Auckland Airport. This is unlikely to be practical or acceptable to Auckland Airport.

Our findings on the current capacity

14.42 We find that the best information on forecasts of demand for jet fuel at Auckland Airport is contained in the 2018 Capacity Review. The Jet Fuel Demand Forecast in that report showed that demand has increased rapidly over the last four years and is currently tracking above the base case and closer to the high-case forecast, with average growth of around 3.5 to 4% each year.

14.43 The Inquiry has concluded that forecast growth in the range of 3.5–4% is a realistic assessment of the likely future demand and is a prudent forecast to work with when assessing the resilience of the fuel supply chain. On this forecast, Auckland Airport will need somewhere between 600 and 900 million litres of additional jet fuel by 2030, and between 1.2 and 1.8 billion litres of additional jet fuel by 2040.

14.44 When the amount of storage is set against average demand, the whole of the supply chain (the total of the tanks at the refinery, Wiri, and the JUHI) currently has between 10 and 14 days of jet fuel in storage, depending on the stage of the supply cycle.

14.45 We have concluded that the capacity of three parts of the supply chain has not been able to keep pace with demand:

- At Wiri, days’ cover has been reducing and now averages a little over four days – about 60% of the level in 2014. Before a batch of jet fuel arrives, it is just above three days and it is forecast to fall below three days by 2022.

- At the JUHI, the two new tanks installed in 2013 have not been enough to maintain capacity in the face of the increasing demand. Cover is now around two days in an average month, under two days during peak months, and projected to drop further.

- On the WAP, Hale & Twomey’s analysis suggests that it will not be feasible to pump enough jet fuel to meet daily demand in the peak month of January – by 2021 on the high case of the Jet Fuel Demand Forecast, and by 2023 on the mid case. This is supported by Z Energy’s analysis.

14.46 In addition, the storage capacity for jet fuel at Wiri and the JUHI will be reduced for essential tank maintenance that is scheduled at various times over the next four years.

14.47 In theory, it might be possible to supplement the WAP’s capacity by trucking up to 0.8 million litres of fuel a day to the JUHI. However, in our view this is unlikely to be a plausible option at the moment for maintaining normal supply, other than for modest amounts in peak months. We accept that Auckland Airport would find it unacceptably disruptive to its operations for large numbers of trucks to be travelling to and from the JUHI, other than in exceptional circumstances.

14.48 The other main part of the supply chain is the RAP. The Inquiry finds that Refining NZ has a clear picture of the forecast increase in jet fuel demand at Auckland Airport and has series of projects underway that are focused on ensuring the RAP can meet the forecast increase in demand. If its planned improvements to the RAP’s capacity are implemented (that is, the introduction of a drag-reducing agent to ground fuels and an increase in the maximum operating pressure to 82 barg), Refining NZ has told the Inquiry it is confident that the RAP will have sufficient capacity to manage the forecast increase in demand through to 2030 and beyond.

15. Is the jet fuel supply chain sufficiently resilient?

15.1 In our view, the answer to this question is simple: no. In this chapter, we explain why we reached that conclusion.

The standards used to assess resilience

15.2 As noted in chapter 3, the Inquiry asked Fueltrac to assess the current and reasonably expected future security of the Auckland fuel supply chain, with a particular focus on jet fuel. Fueltrac used the following standards for that assessment:

- storage close to the airport;

- input supply capacity, compared with peak days’ demand;

- the total days’ cover in the supply chain compared with resupply time; and

- diversity of supply.

15.3 We consider the first three standards in this chapter. Diversity of supply is considered in chapter 17.

Storage close to the airport

How to determine an appropriate storage target

15.4 Storage close to market – in this case, close to Auckland Airport – is an important protection against disruption because the fuel is close to where it is going to be used. The International Air Transport Association (IATA) has published guidance, which includes a framework for assessing the appropriate amount of fuel to store at an airport (the “IATA Guidance”).[31]

15.5 The IATA Guidance shows that the appropriate amount varies, depending on the particular characteristics of an airport. A benchmark of three days’ cover is considered acceptable if the airport is supplied by a pipeline.[32] However, greater on-airport storage may be needed, depending on the level of risk associated with that supply chain.

15.6 For example, IATA notes that the Hong Kong Government requires Hong Kong International Airport to maintain 11 days’ projected jet fuel demand on-airport, given the particular vulnerability of Hong Kong’s fuel supply chain.[33]

Setting a storage target for Auckland Airport

15.7 We concluded that Auckland Airport should aim to store enough fuel to enable it to operate for 10 days at 80% of the fuel allowances for peak days. Auckland Airport is unusual because the Wiri storage facility is only 6 kilometres away. We consider it reasonable to consider Wiri and the JUHI together when assessing the amount of jet fuel storage close to the airport. However, we stress that this approach depends on there being a reliable method of transporting enough jet fuel from Wiri to the JUHI, to enable optimal use and operation of the JUHI storage.

15.8 During the workshop on 30 May 2019, most of the invited participants accepted this was an appropriate resilience standard. The Inquiry agrees because:

- it falls within the range set out in the IATA Guidance and within the range that Fueltrac advised would be reasonable;

- it took 14 days for fresh jet fuel to reach the JUHI after the 14 September 2017 RAP outage;

- Refining NZ advised the Inquiry that in a one-in-20-year event that causes an outage along the RAP, it would expect to have the RAP repaired within 9–10 days;

- there is no alternative jet fuel supply chain to Auckland Airport; and

- Marsden Point refinery is some 170 kilometres from Auckland Airport.

15.9 We emphasise that this resilience standard is based on the particular risks associated with the existing jet fuel supply chain (in particular, single point of failure risk). If, for example, a second, permanent jet fuel supply chain to Auckland Airport were to be established, there could be a basis for reconsidering the appropriate standard for storage at Wiri and the JUHI.

15.10 We received differing views on how peak days’ demand should be calculated for these purposes. The options were:

- the daily average demand for jet fuel across the peak month of a calendar year;

- the actual peak day;

- the thirtieth-highest day over a 12-month rolling average; or

- the average of the top 30 non-contiguous peak days in a calendar year.

15.11 Of these, the Inquiry preferred the last option: the average of the top 30 non-contiguous peak days in a calendar year. This standard, which was supported by Fueltrac, represents a sensible middle ground.

15.12 Fueltrac assessed the current days’ cover at Wiri and the JUHI at the low point of the supply chain to be around six days. BP, the JUHI operator at Auckland Airport, indicated that this figure seemed reasonable.[34] It also aligned with the information contained in the recent Hale & Twomey reports. Whichever way the peak days’ demand was defined, this assessment fell well below the minimum standard that we are proposing.

15.13 The joint venture participants (the fuel companies) that are responsible for storage advised the Inquiry that it takes several years to build major new fuel infrastructure because:

- before approving large projects for Wiri, the WAP, and the JUHI, the joint venture participants follow a set process that is lengthy and involves multiple gateways;[35]

- once a project is progressed through all the gateways and the three fuel companies have made financial commitments, it takes two to three years to build new tanks; and

- it would take approximately four years to construct a second WAP, including around two years to obtain the relevant resource consents.

15.14 Given that discussions are still at an early stage on additional storage at or close to the airport, it could be three to five years before there is more storage built and ready to be used. This is of concern to the Inquiry, given the drop in days’ cover that has already taken place and the rate at which it is forecast to continue to decline. In our view, there needs to be a commitment to build additional storage at Wiri and the JUHI without delay.

Input supply capacity into the JUHI, compared with peak days’ demand

15.15 The Inquiry spoke with Melbourne Airport, which has recently agreed a new ground lease with the fuel company operators of its JUHI. The lease includes a performance standard that requires that the combined input capacity of the pipeline and other supply options (mainly trucking) into the JUHI exceeds 110% of the peak days’ jet fuel demand[36] throughout the term of the lease.

15.16 For example, if the peak days’ demand is forecast to be 10 million litres of jet fuel, the combined input capacity of the pipeline and other supply options should be more than 11 million litres of jet fuel.

15.17 Fueltrac advised that, from a resilience perspective, this is a reasonable standard for the capability of the supply systems to meet peak demand. It includes some spare system capacity to allow for such issues as supply chain outages or delays in transportation.[37]

15.18 The information provided to us showed that the combined input capacity of the WAP and the trucking facility into the JUHI currently exceeds this input standard.[38] However, if the trucking capacity is removed from this calculation, the WAP, by itself, does not meet the desired input standard.

Total days’ cover in the supply chain versus resupply time

15.19 This standard assesses whether the total days’ cover in storage (over the whole supply chain) is sufficient to meet the estimated resupply time. As noted in paragraph 14.9, Fueltrac assessed the total days’ cover at the low point of the supply cycle as approximately 10–14 days. Accordingly, the amount of days’ total cover appears to be around four days short of the best-case resupply time, if a disruption or outage were to occur at the low point of the supply cycle.

Our findings on whether the supply chain is sufficiently resilient

15.20 Putting all of this information and analysis together, we have concluded that the jet fuel supply chain to Auckland Airport is not sufficiently resilient for such an important piece of national infrastructure.

15.21 We have concluded that the appropriate resilience standard for storage should be sufficient storage volume between the JUHI and Wiri to provide 10 days’ cover at 80% of peak operations, calculated on the average of the 30 non-contiguous peak days across the year.

15.22 Applying this resilience standard:

- currently, there is not enough jet fuel storage at Wiri and the JUHI to provide an appropriate level of cover; and

- the amount of cover is forecast to continue to decrease if there is no investment in additional infrastructure in the near future.

15.23 We have concluded that the appropriate resilience standard for input capacity into the JUHI is that it should maintain capacity of 110% of peak days’ demand. Applying this resilience standard to the WAP alone, it already does not meet it. Moreover, the WAP is close to reaching its capacity limit and soon it will not be able to meet the demand.

15.24 The resilience standard is met if trucking capability is included. However, we consider that trucking should not be relied upon at the moment for the transfer of significant quantities of jet fuel (which would require many trucks), given Auckland Airport’s view on the disruption that it would cause to the airport’s normal operations around the domestic terminal.

15.25 In our view, investment is required immediately to increase the input capacity into the JUHI in ways other than trucking. Urgent decisions are also needed on the construction of new storage tanks.[39]

15.26 This conclusion is consistent with the various Hale & Twomey reports that were provided to the Inquiry. In those reports, Hale & Twomey repeatedly noted that:[40]

- additional jet fuel tanks will be required at the Wiri terminal between 2020 and 2025 to manage peak supply months;

- the WAP pipeline system is nearly at capacity; and

- extra storage capacity is likely to be required at the JUHI to maintain sufficient buffers.

15.27 As noted in the 2018 Capacity Review, the amount of stock cover at the Wiri terminal and the JUHI does not provide nearly as much protection as used to be the case, even as recently as 2014.[41]The 2018 Capacity Review added that, had the 2017 RAP outage occurred in 2014, the most severe allocation percentage for the airlines would have only needed to be 50–60%, rather than 30%.[42]

16. Will the needed investment be made in a timely way?

16.1 In this chapter, we explore the reasons for the decline in the resilience of Auckland’s jet fuel supply chain and whether future timely investment to improve its resilience is likely to occur.

Why has resilience declined?

Significant growth in jet fuel demand

16.2 As already explained (see paragraph 14.13), jet fuel demand at Auckland Airport has effectively doubled over the last 20 years, with nearly half of that growth occurring in the last four years. The recent growth apparently took the industry by surprise. Nobody had forecast this significant level of increase.[43]

Uncertainty about the relocation of the JUHI

16.3 Over the past decade, Auckland Airport has been considering decommissioning the current JUHI site and moving it to a different location at the airport, because the present JUHI location is incompatible with their plans to relocate the domestic terminal and expand regional airline services.

16.4 In 2007, Auckland Airport carried out a review (in conjunction with fuel company and airline stakeholders) to determine the best possible site for a new JUHI. The preferred site was Orrs Road, mainly because it is close to Wiri and it would be easy to connect it to the WAP. Auckland Airport obtained planning permission and a designation to enable a new JUHI to be built there.

16.5 Auckland Airport told the Inquiry that their thinking has evolved significantly in the light of their major expansion plan. They had recently convened an industry working group consisting of representatives from BP, Mobil, Z Energy, BARNZ, and Air New Zealand (with support from WorleyParsons) to look at the location issue again. This working group is providing advice and input into Auckland Airport’s process for making a final decision on the location of the new JUHI. Three sites are being assessed (including Orrs Road).

16.6 Although Auckland Airport had previously expressed an intention that the existing JUHI would continue to operate until 2035, the JUHI joint venture participants repeatedly raised concerns with us about the possibility that the lease could be terminated early. The Airport Authorities Act 1966 includes a statutory power for an airport to terminate such a lease at any point, without compensation, although we are unaware of any instances where an airport has successfully used this power.

16.7 The JUHI participants said they were unlikely to make decisions to invest in new and expensive infrastructure at the current JUHI location if they did not have more certainty that the lease would continue. Otherwise, they saw a risk that they would be left with a “stranded asset” that was not able to generate a return on the initial investment.

16.8 This issue was raised again at the forum we held, where Auckland Airport stated they had no intention of ending the lease early.[44]In our view, this assurance should be sufficient to resolve the concern of the JUHI joint venture participants.[45]

Sector governance and joint venture arrangements

16.9 The qualities of a resilient system include good governance and effective leadership that ensure investment and actions are appropriate and timely.

16.10 The Inquiry understands that joint ventures can have strong community benefits: they can be used to provide a product or service more efficiently than when the product or service is provided by separate entities. Joint ventures can provide efficiency gains from economies of scope and scale, and can help to avoid the high costs associated with duplication of assets.[46]

16.11 However, joint ventures also have their disadvantages. The Inquiry believes that for several reasons, the current joint venture governance arrangements for the Wiri terminal, the WAP, and the JUHI have been a significant contributing factor in the reduction of the resilience of this infrastructure.

16.12 First, the separate arrangements at each point of the supply chain result in a very complex ownership and governance structure. We described these in chapter 2 and illustrated them in Figure 2.

16.13 Second, investment decisions should be timed so that step changes are six months too early, rather than two years too late. Our perception from the fuel companies that make up the three joint ventures in the single jet fuel supply chain is that they are focused on meeting the demand curve (or, as is the current situation, catching up with the curve after a rapid increase in demand). We note the observation in the 2018 Capacity Review:[47]

While forecasting is uncertain and outside factors can make sharp (positive and negative impacts) on demand, planning for next investment steps should be done in advance. This is done for RAP, with work now being undertaken on the steps (stages) of future investment to capture an additional 40% capacity. [It] would appear that this is not the case for Wiri Terminal and Auckland JUHI, although work has been done to ensure there is the ability to expand Wiri Terminal under council planning and zoning changes. It would seem sensible that these facilities also have future investment stages identified and planned for, so that once certain triggers are reached (e.g. after investment now, should resilience fall to 2014 levels again), then the next investment step could be actioned.

16.14 We agree with these comments. In fact, the Inquiry finds them particularly concerning in the light of the sharp drop in the resilience provided by the storage at Wiri and the JUHI in recent years, driven by unforecast growth in demand at Auckland Airport, and the fact that lead times for deciding on and building new infrastructure are long (for example, three to five years in total).

16.15 Third, the joint venture arrangements for Wiri, the WAP, and the JUHI usually require unanimous agreement by all three fuel companies to make investment decisions: that is, three different companies with three different internal decision-making processes, priorities, risk appetites, and opinions on what is economically feasible.[48]

16.16 The decision-making process for investment in the Wiri terminal requires each fuel company to individually instruct WOSL to proceed to a “gateway” for a project (for example, preparing a business case to +/− a certain part of the budget), rather than instructing WOSL as a group. There are multiple gateways and WOSL can usually only proceed with the unanimous approval of all shareholders at each point.[49]

16.17 This process ensures careful consideration of all options and produces robust business decisions. However, it also slows down decision making on major investments. The delays associated with this decision-making process must be factored into the joint venture participants’ investment planning.

16.18 During this Inquiry, the fuel companies showed that they do not currently agree on where and how much investment is required. Table 10 illustrates this, setting out the various positions of the parties in their written submissions and oral submissions during the forum.

16.19 The Inquiry has been advised that in Australia, vertically integrated oil companies, operating strategic jet fuel infrastructure under identical arrangements, have been slow to provide capital for new infrastructure investments.[50]The Australian Productivity Commission has made similar comments in its draft report, the Economic Regulation of Airports,[51] as did Melbourne Airport when we spoke to them.

Table 10: Summary of the joint venture participants’ written and oral submissions at the forum

|

|

BP |

Mobil |

Z Energy |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Wiri terminal |

BP told the Inquiry that it would be sensible for additional jet fuel storage to be established at the Wiri terminal. It proposed two new 11 million litre tanks at the Wiri terminal, to provide additional cover of approximately 4–5 days. Provisional funding has been approved in its capital plans for its share (28%) of the capital cost for constructing these two tanks, subject to an approved business case. Once all of the WOSL shareholders have provided funding approval, it will take around two years to build these tanks. |

In its written submission, Mobil told the Inquiry that one form of future investment in additional storage might be required at or near Auckland Airport if actual demand follows the Jet Fuel Demand Forecast. The timing, location, and configuration of additional storage are yet to be determined and are dependent on market demand. There are, however, preliminary concepts for additional jet fuel storage tanks at WOSL. |

Z Energy is investigating having more tanks at Wiri and is currently exploring options to build three 13 million litre tanks on Roscommon Road. Z Energy was unsure whether two 11 million litre tanks would be sufficient to build resilience, and there might still be a deterioration of resilience based on jet fuel demand growth. Z Energy has pre-approved capex to invest in the supply chain to a material degree, but exactly where and how is still to be finalised. |

|

JUHI |

BP told the Inquiry that additional jet fuel storage is required at the existing JUHI prior to the expiry of the lease there (in 2035). It would take 2–3 years to build additional storage at the JUHI once all parties have provided funding approval. However, Auckland Airport has the ability to terminate the JUHI lease without compensation (under the Airport Authorities Act 1966). |

In its written submission, Mobil said the existing JUHI participants are currently considering a preliminary business case for additional storage at the JUHI. This is at an early stage and will need to consider a number of factors, including land availability, land tenure, and funding. |

Z Energy told the Inquiry there is an opportunity to increase storage at the JUHI, although the probable move of the facility by 2035 likely makes this option economically infeasible. |

|

WAP |

BP is open to considering the feasibility of a second WAP. However, it would prefer installing additional loading capability and significantly increasing transportation to the JUHI via truck. It would not be commercially feasible for a single entity to fund these options. The better option is to increase the capacity of the existing WAP. |

Mobil said that additional WAP capacity may be required if actual demand follows the Jet Fuel Demand Forecast. It is not necessarily supportive of duplicating the WAP, noting, “[d]uplicating the WAP necessarily involves a large one-off capital investment that will deliver substantial excess capacity once complete, resulting in substantial capital inefficiency and unnecessary costs for consumers”. Mobil is, however, supportive of continued development and optimisation of truck-bridging capability between Wiri and the JUHI. |

Z Energy said a second WAP along the current easement is needed for all resilience scenarios. This would address the single point of failure risk of transferring jet fuel between Wiri and Auckland Airport and mitigate the current concern of reduced days’ cover at the existing JUHI facility. It said the WAP is the biggest current constraint on supply to the airport. Investment in a second WAP would provide the “best bang for the buck”. It considers that any solution involving trucking is not a reliable, efficient, safe, or environmentally sustainable option for jet fuel. Z Energy would prefer to invest in a second WAP before building more storage at the JUHI. |

|

CASE STUDY: MELBOURNE AIRPORT[52] The JUHI at Melbourne Airport is operated under a joint venture arrangement between the four major oil companies: BP, Viva (previously Shell), Exxon Mobil, and Caltex. The JUHI is supplied by a pipeline owned by a different consortium of oil companies and an independent investor. There are also facilities at the airport that allow unloading at the JUHI by truck. Melbourne Airport told us that the oil companies were aware of the rapid growth in jet fuel demand at Melbourne Airport for international long-haul demand from 2014 onwards (passenger growth consistently 10% per annum). However, the pipeline owners and the JUHI joint venture participants had not made any investments to increase the input capacity into the JUHI or increase the on-airport storage. Separately, Mobil told us that for a period, there was only eight hours’ jet fuel stock cover at the Melbourne Airport JUHI. We understand that during certain periods in 2016 and early 2017, the peak days’ demand exceeded input supply capacity to the airport and jet fuel rationing was required. Negotiations with the oil companies were already underway because the JUHI ground lease was about to expire. Melbourne Airport informed us that it had decided that it wanted a new agreement that, among other things, would ensure there was enough input capacity and on-airport storage to meet Melbourne Airport’s current and future needs. Melbourne Airport said it had escalated this issue and engaged the support of the Victorian State Government when a new-entrant airline, which intended to provide services between Asia and Melbourne, decided to pull out from Melbourne Airport because it could not obtain jet fuel. The Victorian Government formed a round table working group with key industry stakeholders.[53] Melbourne Airport and the four major oil companies negotiated a new lease agreement in 2018, which prescribed (among other things) safeguards to ensure continued investment in the JUHI facilities, covering input capacity, onsite storage, fuel hydrant infrastructure, and open access, to promote competition in the fuel supply at Melbourne Airport. The new agreement required that:

A process is in place for determining when investment needs to occur in the JUHI facility and associated fuel hydrant network. Melbourne Airport told us that it meets with the JUHI operating committee monthly, quarterly, and annually, and as part of that process, the parties map out the jet fuel demand forecasts for the next five years. Where the forecasts show that capacity is getting close to falling below the threshold, the operating lease factors in a lead time of up to three years (depending on the infrastructure), to enable the JUHI joint venture participants to plan and construct infrastructure to address the forecast demand increase. The operating licence also requires the JUHI to implement an open-access regime to enable suitably qualified industry participants to apply for access to the JUHI facility to provide jet fuel. Failure to deliver these requirements can result in a breach of the operating licence. |

What investment is likely?

16.20 The Inquiry asked the relevant participants about their investment plans for the infrastructure that makes up the Auckland jet fuel supply chain. In this section, we summarise what they told us.

Marsden Point refinery and the RAP

16.21 Refining NZ intends to convert a tank from diesel to jet fuel at the Marsden Point refinery to meet increasing demand and for jet fuel imports. The conversion requires the diesel tank to be completely refurbished, including the replacement of the tank roof and the addition of a special coating to the tank’s interior. The Inquiry understands that this project will add an additional 18 million litres of jet fuel storage.

16.22 Refining NZ is also taking steps to increase the capacity of the RAP, including:

- trialling the use of drag-reducing agents in diesel and gasoline, as explained in Paragraph 2.38;

- increasing the maximum operating pressure to 82 barg; and

- investigating whether a further material increase in capacity could be achieved by installing three additional intermediate pump stations along the RAP. This work is at an early stage, but potential parcels of land are being identified for the additional pump stations.

16.23 Based on this information, we are satisfied that Refining NZ is working to make timely investment decisions. They have a clear goal of having new infrastructure in place shortly before it is needed to meet demand, rather than just in time or too late. We are satisfied that investment is likely to take place so that the resilience of these facilities to meet the stress of increasing demand is not reduced.

The Wiri terminal, the WAP, and the existing JUHI

16.24 The same cannot be said about the Wiri terminal, the WAP, and the existing JUHI. As the Inquiry found, there has been a significant decline in the resilience provided by these facilities.

16.25 The Inquiry understands that there is a project currently underway to upgrade the automation capability of the WAP.[54]This is, however, only an operational improvement and we understand it will provide only an incremental increase of approximately 5% in the volume of jet fuel that can be transferred each day. Some work is also being done to determine the maximum flow rate capacity down the WAP.[55]

16.26 The three fuel companies that are the joint venture participant owners of the Wiri terminal, the WAP, and the JUHI have so far not committed to the investment we think is needed to achieve and maintain the minimum resilience standards they agree are appropriate.

16.27 In early July 2019, following the Inquiry’s workshop and forum sessions, we were told that the three major fuel companies have agreed to advance a Front-end Engineering Design for additional tanks at Wiri, which is the first gateway in their decision-making process. While they have committed to and started a process for investing in tanks, they have not been able to give the Inquiry confidence that the needed investment will occur. They could not give us any estimate of how long this decision-making process would take, nor any definite commitment that tanks would actually be built at the Wiri terminal. Nor could they provide the Inquiry with a definite commitment that they would invest to increase the capacity of the WAP or storage at the JUHI.

16.28 At the workshop and forum sessions, the airline representatives and Auckland Airport stated their concern that there was a lack of transparency of information from the joint venture participants about their planning and timelines for investing. Given the now obvious need for additional infrastructure to respond to forecast increases in jet fuel demand, they said it was creating significant customer uncertainty. The Inquiry endorses this concern.

Our findings on whether investment is likely to occur

16.29 We have concluded that the reduction in the resilience of the Auckland fuel supply chain since 2014 has resulted from a combination of:

- the significant growth in jet fuel demand over the last four years, which was not forecast by the three fuel companies that are the joint venture participants for most of the relevant infrastructure;

- the lack of consensus between the fuel companies that own the Wiri terminal, the WAP, and the JUHI on what investment needs to occur, and when, in relation to those pieces of infrastructure; and

- uncertainty about the timing for the relocation of the current JUHI to a new location and about where the new JUHI will be located.

16.30 The Inquiry is satisfied that Refining NZ is likely to make timely investment decisions to ensure the capacity of the Marsden Point refinery and the RAP will continue to meet forecast increases in jet fuel demand.

16.31 We are not satisfied that the three fuel companies that own the Wiri terminal, the WAP, and the JUHI will make timely decisions to invest in needed infrastructure.

16.32 We have now identified the minimum quantities of storage and input capacity that we regard as appropriate resilience standards. We expect the major fuel companies that own this infrastructure to commit to work towards meeting these resilience standards.

16.33 The Inquiry observes that the lead time for making a decision and building large infrastructure such as storage tanks can be as long as three to five years when the joint venture decision-making process to begin a project is included. Even if the companies make decisions to invest in new storage tanks and additional input capacity this year, neither will come on-stream for some years. By that time, the resilience assessment will be even lower than it is now.

16.34 It appears that the debate and interaction created by our Inquiry work may have raised the profile of these issues with the three major fuel companies. The documents they have recently provided suggest an increased focus in the last few months. However, they are still some way from any confirmed decisions to invest in new infrastructure.

17. Alternative methods of supplying jet fuel to Auckland Airport

There is no permanent, second supply chain for jet fuel to Auckland Airport

17.1 We identified that diversity of supply – having alternative ways of bringing fuel to a market – increases the resilience of the fuel supply system (see Table 3). Unfortunately, at present there is no permanent second supply chain for jet fuel to Auckland Airport. The supply chain is vulnerable to single point of failure risk all the way along it.

17.2 We compared Auckland Airport to other airports in Australia, namely Sydney, Brisbane, Melbourne, and Perth. We make the following observations:

- Sydney, Brisbane, and Melbourne have diversity of supply of jet fuel to the airport.

- If there were a long-term fuel disruption event in Sydney and Melbourne, the second supply chain could be scaled up.

- The JUHI at Brisbane Airport is supplied by two pipelines, from different directions and using different pipeline easements. The capacity on each of these pipelines exceeds total daily airport demand. Accordingly, if one of the pipelines were to suffer a long-term outage, the other could supply all the fuel the airport needs.

- By contrast, Perth, like Auckland, is vulnerable to a single point of failure risk. It has one dedicated fuel pipeline as its single source of supply of jet fuel.

17.3 Auckland Airport is roughly comparable to Brisbane Airport in terms of the total number of aircraft movements, the total number of passengers, and jet fuel consumption.

17.4 We note that Perth Airport has expressed concern about the potential single point of failure risk along its fuel supply chain. It identified “security of supply” (including “multiple modes of fuel delivery and adequate on-airport storage to mitigate the risk of supply disruption”) as a core principle that should apply to its jet fuel supply chain.[56]

17.5 Each airport is different and jet fuel supply chains to airports are usually the result of historical decisions, rather than deliberate design from a resilience perspective. However, this should not distract from the fact that Melbourne, Sydney, and Brisbane have diversity of supply. Auckland and Perth do not.

17.6 During the closed workshop and the public forum, most participants considered that the development of a permanent, second, independent jet fuel supply chain, if that was possible, would be the most effective method of enhancing resilience. Participants told us that a second supply chain would:

- enable continuity of supply in all disruption scenarios;[57]

- mitigate the single point of failure risk along the existing Auckland jet fuel supply chain; and

- enhance the resilience of the jet fuel supply chain in the face of disruptive events that last more than 10 days.[58]

17.7 The 2018 Capacity Review also noted the significant difference an alternative supply chain can make, even if it only caters for a small amount of an airport’s total daily demand for jet fuel:[59]

During the 2017 RAP outage, airlines were initially allocated 30% of normal demand at Auckland Airport. If an alternative supply option could meet 10% of normal demand, this would provide significant benefit during a disruption. As an example, for the 2017 RAP outage this may have resulted in 40% allocations which would have been a 33% increase in supply to the airlines.

17.8 In addition, during the forum, BARNZ told us that new-entrant airlines considering providing services to an airport would carry out a risk assessment of that airport, including consideration of the availability and security of jet fuel. It noted that a second jet fuel supply chain is one of the structural points that airlines take into account when considering this risk.

17.9 We also heard that a permanent second supply chain is preferable to back-up supply chains that can only be used in the event of a disruption. If the second supply chain is already established, then no time is lost in setting up supply. Fueltrac identified a number of possible sources of delay when setting up a temporary, back-up supply chain, including time lost in:[60]

- the recommissioning of temporary trucking facilities;

- converting tanker trucks from diesel to jet fuel service by modifying couplings and cleaning them (which usually takes three to four days);

- finding appropriately qualified and trained drivers;

- training people to operate the back-up system; and

- repositioning trucks and drivers to initiate the emergency response.

17.10 Further problems with back-up supply options are that:

- infrastructure and machinery set aside for emergency use may not have been regularly used or tested, which could mean delays in making it operational; and

- although diesel trucks can be modified, this can create issues with the ongoing supply of ground fuels in an emergency situation because the trucks would no longer be available to transport diesel. As BP cautioned, “It should not be assumed that ground fuel supply will necessarily be able to be sacrificed to meet jet fuel requirements”.[61]

17.11 The delays associated with establishing a back-up supply chain were demonstrated during the RAP outage:

- It took eight days to construct a temporary jet fuel loading gantry at the Marsden Point refinery so that jet fuel could be trucked from the refinery.

- It was 12 days before trucks could begin supplying the JUHI from Wynyard Wharf.

17.12 For these reasons, we concluded that the establishment of a permanent second jet fuel supply chain to Auckland Airport (independent of the RAP, the Wiri terminal, and the WAP) would enhance the resilience of the jet fuel supply to Auckland Airport.

Is someone likely to invest to create a second supply chain?

17.13 Several participants spoke to the Inquiry about the possibility of establishing a second supply chain for jet fuel. This was encouraging, even though all of the thinking is still at a preliminary stage.

17.14 None of the participants suggested that they were considering construction of a second RAP. Fueltrac gave us a ballpark estimate that a new pipeline to duplicate the RAP could cost around $425 million.

17.15 Nor are any parties considering shipping jet fuel to a port in Auckland. With the Wynyard Wharf facilities gone, there does not appear to be any other suitable land for storage tanks in the port area in central Auckland. We were also told it is not particularly desirable to put fuel storage close to residential and office accommodation.

17.16 However, two other options for alternative supply chains were discussed during the forum sessions:

- a trucking option from Marsden Point or Mount Maunganui (being explored by Gull); and

- a rail option from Mount Maunganui (being explored by Z Energy, BP, and Mobil as part of the Auckland Jet Fuel Resilience Group).

Trucking option from Marsden Point or Mount Maunganui (Gull)

17.17 Gull informed the Inquiry that it intends to enter the Auckland jet fuel market within the next one to three years. It proposes to do so by establishing a second jet fuel supply chain by importing refined jet fuel into a New Zealand port and trucking it to Auckland Airport. It has investigated two possible ports:

- Marsden Point, where it would build a truck load-out facility next to the refinery; or

- Mount Maunganui, where it would build jet fuel storage tanks and a load-out facility.

17.18 During the forum, Gull told the Inquiry that it had applied to join the JUHI at Auckland Airport so it could truck the jet fuel to the JUHI and feed it into the hydrant system from there. There is no other way of providing any significant volume of fuel to airline customers. However, Gull did not yet know what the likely cost would be.

17.19 In a submission we received after the forum, Auckland Airport advised that it does not consider trucking fuel to the JUHI to be a viable option, for traffic management reasons. Specifically, Auckland Airport told us:[62]

Auckland Airport’s core aeronautical precinct is not designed to support regular large format trucks or high volumes of trucking. Within the last 12 months Auckland Airport has invested specifically to remove truck movements from the core precinct by developing a peripheral road link specifically for this purpose and implemented heavy vehicle restrictions and penalties pursuant to the Auckland International Airport bylaws for unauthorised access. Every tanker truck delivery would involve traffic management, in particular the complete closure of the core precinct’s domestic terminal access roads twice for each truck delivery (i.e., 20 road closures per day to facilitate 10 tanker truck deliveries). The impact of this would be significant given 50% of all passengers use the domestic terminal.

17.20 Auckland Airport would prefer that any trucked jet fuel be delivered to Wiri (although at present, Wiri cannot receive fuel from trucks). We understand that it has conveyed this view to Gull as well.[63] However, Mobil told us:[64]

Whilst recognising trucking to Auckland Airport may impact traffic flow, this option should be explored ahead of trucking upstream of the JUHI. It has already been concluded that having a second supply chain enter the system as close to the airport is preferable. Trucking upstream of the JUHI puts more strain on existing infrastructure downstream of where the trucking layer enters and reduces the overall resilience of the trucking layer.

17.21 In the Inquiry’s view, trucking may be inevitable in the short term, given the capacity constraints we have identified with the WAP and the time that it would take to build a second WAP.

17.22 As discussed in paragraphs 16.3–16.8, the existing JUHI needs to be moved to a new site to accommodate the relocation of Auckland Airport’s domestic terminal and expansion of regional airline services. Auckland Airport is in the process of making a final decision on the location of the new JUHI. It is important that the final decision about its location takes into account resilience considerations, including the ability to supply jet fuel to the Airport via a permanent second supply chain, whether via truck, train, or another method of supply.

Train option from Mount Maunganui (Z Energy, BP, and Mobil)

17.23 During the forum, Z Energy told the Inquiry that it had identified the possibility of transporting jet fuel from Mount Maunganui to Auckland Airport using rail. This option would require:

- the conversion of tanks at Mount Maunganui to store jet fuel;

- the construction of new rail loading infrastructure (at Mount Maunganui) and discharge infrastructure (at Wiri); and

- the construction of infrastructure to transport jet fuel from the rail siding at Wiri to Auckland Airport.

17.24 Z Energy told the forum that:

- it had been talking to existing joint venture participants, but the option could also involve new participants;

- it had done enough work with the other joint venture participants to establish that this option is operationally feasible, including speaking to both KiwiRail and the landowner of the discharge point at Wiri;

- it would take several years to deliver this option; and

- the fundamental question was whether this represents a reasonable amount to spend on improving resilience for a high-cost, low-probability event like the 2017 RAP outage.

17.25 The Inquiry understands that this option has been the subject of discussion as part of the Auckland Jet Fuel Supply Resilience Group.However, the focus of the group has recently shifted to shorter-term options that BP, Mobil, and Z Energy may be able to agree on as a minimum.[65] BP informed us that the Group is continuing to consider the Mount Maunganui jet fuel supply option as well.

17.26 The consideration of these options is still at an early stage. All of them would involve a substantial commitment of energy and money. We do not have a view on whether any of the companies considering these possibilities, or others, will ultimately invest in them. Under the current industry settings, it is for the participants in the market to decide what is financially viable for them.

Are there barriers to investment in an alternative jet fuel supply chain?

17.27 We have noted that some parties are considering the possibility of investing in a second supply chain. Aside from the economics of that decision, we asked whether there were other barriers that might prevent or inhibit such an investment.

17.28 The WAP and the JUHI operate under what is known as a restricted-access regime. Restricted access means that jet fuel suppliers cannot simply pay a fee to access the infrastructure but are required to purchase an equity stake in it before they are given access. Accordingly, in order to obtain access to the WAP and the JUHI, a new entrant would be required to pay a purchase price for a share in the infrastructure. An accession process, with qualifying criteria, is set out in the joint venture agreements for the WAP and the existing JUHI (which we have seen). Ultimately, it is for the Operating Committee for each piece of infrastructure, made up of the existing joint venture participants, to decide whether to grant access to the new entrant.

17.29 The Inquiry is not aware of a set process governing how third-party jet fuel suppliers can access the facilities at Wiri. However, a potential new entrant can always attempt to negotiate access with the current owners.

17.30 In our view, these access regimes create barriers for new entrants to the jet fuel supply market, as explained in the following sections.

Conflict of interest

17.31 Wiri, the WAP, and the existing JUHI are each the subject of a joint venture arrangement. Key decisions of the joint venture participants usually require unanimity.[66]

17.32 The jet fuel supply chain is also the subject of vertical integration. BP, Mobil, and Z Energy are involved in each part of the supply chain, from the importing of crude oil through to delivery of jet fuel into the plane. In other words, they are responsible for the importing, storage, transfer, and sale of jet fuel at each stage of the supply chain.

17.33 Other fuel suppliers who are looking to access Wiri, the WAP, or the existing JUHI would be competing for the three incumbents’ customers (that is, the airlines) at the end stage of the supply chain when the fuel is sold. This gives rise to a conflict of interest: there is an incentive for the incumbent joint venture participants to deny or inhibit access to new entrants who will compete with them as sellers of jet fuel.[67]

17.34 We acknowledge that Caltex was admitted to the WAP and the JUHI in the late 1980s. We are not aware of any other example of a party seeking admission to the JUHI in New Zealand (other than Gull’s current application).[68]

The requirement to purchase an equity share

17.35 The requirement that a new entrant purchase an equity share can create risk for potential new entrants who are in the early days of setting up a supply chain. It is a substantial cost when they are still determining whether they can establish and grow a market, at least when compared with non-equity structures that charge a throughput fee (which provides the incumbent infrastructure owners with a fair rate of return).[69]

Lack of transparency around terms of access

17.36 During the forum, Gull told the Inquiry that it needs to obtain access to the on-airport hydrant system to establish its proposed jet fuel supply chain. At present, access can only be obtained through the JUHI.

17.37 The JUHI joint venture participants have asserted confidentiality over the agreement that governs the existing JUHI. Gull told the Inquiry that it did not know what it needed to do to obtain access to the JUHI other than the first step, which was to obtain approval from Auckland Airport to supply jet fuel. It had no real idea of how long the process would take. We understand that Gull made an application to Auckland Airport for approval on 28 May 2019.

17.38 Gull provided us with an update on their progress in July 2019. They commented that that the entry process had become “frustratingly cumbersome” and a “chicken and egg” scenario. Specifically, Gull told us that the JUHI joint venture participants required Auckland Airport’s approval in order to provide the qualifying criteria; but Auckland Airport would not provide that approval until it had received certain information from Gull; which, according to Gull, could not be provided until it had seen the qualifying criteria.[70] After receiving a draft version of this report, the major fuel companies informed the Inquiry that they have agreed to share the qualifying criteria with Gull, despite it not having been granted approval by Auckland Airport.

17.39 As part of its Inquiry into the Economic Regulation of Airports, the Australian Productivity Commission received evidence on the lack of transparency around access terms to on-airport fuel infrastructure and the difficulties this can create. That evidence was similar to what we heard from Gull during the forum sessions. In its written submission, Qantas submitted:[71]

At most airports in Australia new suppliers can only access on-airport fuel facilities via equity ownership. The process for equity access at a major airport JUHI is complex and time-consuming with little transparency.

17.40 Similarly, Virgin Australia commented in its written submission:[72]

Potential new jet fuel importers are faced with considerable uncertainty and risk about their ability to gain access to the jet fuel infrastructure supply chain. This uncertainty around obtaining secure and coordinated access to the jet fuel infrastructure supply chains is a clear deterrent to new market entrants and increased competition.

Would open access to the JUHI remove these barriers?

17.41 Some participants, as well as Fueltrac, recommended that the Inquiry consider whether open access to Wiri, the WAP, and/or the JUHI would enhance the resilience the Auckland jet fuel supply chain. This matter was an area of focus during the forum sessions and the Inquiry received oral and written submissions on it.

17.42 Open access refers to access arrangements for infrastructure where all the suppliers have equal rights to access the infrastructure through a fee-based, non-discriminatory pricing agreement with the owners or operators of the infrastructure.[73]

17.43 There are many ways open access can be facilitated:[74]

- by agreement between the owners and operators of a terminal, pipeline, or on-airport storage facility;

- by an airport requiring that open access be included as a condition of the ground lease for an on-airport storage facility;

- by an airport investing in the on-airport storage facility itself, and then reaching agreement with a third party to operate the on-airport storage on an open-access basis;

- by an airport reaching agreement with a third party to build, own, and operate on-airport storage on an open-access basis; or

- by government regulation.

17.44 We noted that, in Australia, both Darwin and Melbourne Airports have recently adopted open-access regimes for the JUHIs at those airports:

- At Melbourne, the airport made open access a condition of the ground lease for the JUHI.

- At Darwin, the airport has purchased a 40% stake in the joint venture on-airport storage and hydrant facilities and is buying out the other participants over the next 12 years. As part of this arrangement, Darwin Airport has made these facilities open access.

17.45 During the forum, participants variously submitted that:

- open access is not a resilience issue and is outside the scope of the Inquiry’s Terms of Reference because access to Wiri, the WAP, and the JUHI was not a factor during the RAP outage;[75]

- any new entrant to the existing supply chain would introduce further complexity with respect to product quality, scheduling of batches, and decision making, which would decrease the resilience of the fuel supply chain;[76]

- the link between open access and resilience has not been demonstrated and is not guaranteed;[77]

- the existing access arrangements work effectively and enabled Caltex to join the WAP and the existing JUHI in the 1980s; and

- open access would create uncertainty and diminish the likelihood that the incumbent owners would invest in additional infrastructure.

17.46 The Inquiry considered these arguments carefully. We accept that open access does not guarantee additional resilience along the jet fuel supply chain. However, we were persuaded that it would have the effect of removing barriers to entry that make it difficult for new entrants to set up alternative jet fuel supply chains. We think that open access helps to provide an opportunity for new entrants to invest in infrastructure that could potentially result in diversity of supply and therefore, it has the potential to enhance the resilience of the jet fuel supply chain. We note the following:

- Open access removes the perceived conflict of interest associated with BP, Mobil, and Z Energy, which are all sellers of jet fuel, controlling access to infrastructure that is necessary to enable other third-party suppliers to sell jet fuel to airlines.

- The RAP outage exposed that the jet fuel supply chain is vulnerable to single point of failure risk. One of the key lessons from the outage is that, for resilience purposes, it is desirable that Auckland has a second permanent fuel supply chain. This is especially true now that the primary back-up supply chain that was used during the 2017 is no longer a viable option.

- Gull’s experience in trying to access the existing fuel infrastructure indicates that the requirements to obtain access are murky and cumbersome. A similar experience appears to have been shared by new-entrant jet fuel suppliers in Australia.

- Open access can help to remove the lack of transparency around access arrangements. For example, under the JUHI ground lease at Melbourne Airport, the JUHI joint venture participants are required to publish on their website information for applicants seeking access.[78]

- Open access, with payment of a throughput fee, presents a lower barrier to entry for new entrants in terms of start-up costs (as opposed to the requirement to purchase an equity share).

- Any complexity associated with enabling additional suppliers to use the WAP and the existing JUHI infrastructure appears to have been successfully negotiated when Caltex obtained access to these facilities.

Our findings on the possibility of an alternative method of supply for Auckland

17.47 We have concluded that in principle, the most effective method of enhancing resilience for Auckland Airport’s fuel supply would be the development of a permanent, second, independent jet fuel supply chain, if that was possible. We believe that a permanent supply chain is preferable to back-up arrangements that can only be used in the event of a disruption.

17.48 As noted earlier, several companies are considering the possibility of establishing a second supply chain for jet fuel. We do not have a view on whether any of the companies considering these possibilities, or others, will ultimately invest in them. Under the current industry settings, it is for the participants in the market to decide what is financially viable for them.

17.49 In our view, the access regimes at Wiri, the WAP, and the existing JUHI create barriers for new entrants to set up alternative methods of supply in the jet fuel market:

- The vertical integration of the jet fuel supply chain (where the owners of Wiri, the WAP, and the JUHI are the same companies that sell jet fuel to airlines), along with the ability for the incumbent joint venture owners to control access to that infrastructure, gives rise to a conflict of interest. There is a structural incentive for the incumbent joint venture participants to deny or inhibit access to new entrants that will compete with them for jet fuel customers.

- The requirement that a new entrant purchase an equity share can create risk for potential new entrants that are in the early days of setting up a supply chain and still determining whether they can establish and grow a market (when compared with non-equity structures, which charge a throughput fee that provides the incumbent infrastructure owners with a fair rate of return).

- There is a lack of transparency around the decision-making processes for gaining access to Wiri, the WAP, and the JUHI.

17.50 The Inquiry considers that open access to the infrastructure in the supply chain would have the effect of removing barriers to entry that make it difficult for new entrants to set up alternative jet fuel supply chains. As a result, it has the potential to help enhance the resilience of the jet fuel supply chain.

18. How to improve the resilience of the jet fuel infrastructure serving Auckland

The problem with the current supply chain for jet fuel

18.1 It is in the public interest that the infrastructure that supplies jet fuel to Auckland Airport is resilient. It needs to:

- deal with acute shocks (for example, the sudden rupture of the RAP in 2017), as well as with more gradual stresses (for example, pressures from increasing demand for jet fuel);

- be part of a system that learns from experience (for example, the vulnerability arising from a lack of diversity of supply highlighted by the RAP outage); and

- provide a platform for the Auckland region to grow and thrive (for example, by ensuring that nationally important infrastructure, such as Auckland Airport, can continue to meet New Zealand’s needs, both now and well into the future).

18.2 In this Part, the Inquiry has analysed the single jet fuel supply chain to Auckland Airport and found there is a risk of single point of failure along all parts of the supply chain to the Airport. The Inquiry subsequently concluded that the infrastructure making up this single supply chain is not sufficiently resilient. Its resilience is projected to decrease further in the light of forecast demand in both the short and medium term.[79] In addition, the supply chain is not well placed to manage another outage of any significant duration.

18.3 To recap:

- Refining NZ has a clear picture of the forecast increase in jet fuel demand at Auckland Airport and has a series of projects underway to ensure the RAP can meet the forecast increase in demand. If its planned improvements to the RAP capacity are implemented (that is, the introduction of a drag-reducing agent to ground fuels and an increase in the maximum operating pressure to 82 barg), Refining NZ is confident that the RAP has sufficient capacity to manage increasing demand through to 2030 and beyond.

- The capacity of the infrastructure making up the rest of the supply chain (Wiri, the WAP, and the JUHI) can meet current jet fuel demand, but urgent investment is required if these pieces of infrastructure are to continue to cope with forecast demand across the next few years.